Musings on Psychedelic Medicines

Part I: Science & Society

I ate 25mg of psilocybin before writing this.

Just kidding.

Well, half kidding.

While relocating to London earlier in the year, I was told that there were 3 main categories of items I could not ship overseas: plants, alcohol, and drugs.

I was really upset about the first one. I name my plants and sing to them. Luckily, they were all given excellent homes with friends and family (I even snuck a few into my suitcase – don’t tell UKVI).

The second one I didn’t care much about. I actually made quite a few people happy while giving away the entire contents of my home bar.

The third one wasn’t necessarily a problem. Between caring for a parent with brain disease, watching the opioid epidemic spiral out of control in America, and studying neuroscience, I just know too much. Don’t get me wrong, I have dabbled in a thing or two in my heyday, but Requiem for a Dream scared me enough as a teen that I had limits.

Plants and psychedelics are a totally different story. They’re powerful, sacred medicines. They unblock and heal. They break the boundaries of casual recreation and transform the mind and body in ways that are, for lack of better words, magical.

Don’t worry, this is not some personal account of a mushroom trip and everything it taught me. There are plenty of stories on Erowid and Reddit if you want to bond with others via experiential inspiration. I’m also not blindly following a trend or preaching that you should pour your savings into psychedelics investments. I write about topics I genuinely believe in and have lived experience to back.

That’s why I’m excited to say that the psychedelics renaissance is here. There are many people who have worked diligently and carefully to get us to this turning point – a convergence of curiosity, courage, and crisis.

What’s even more exciting is that the next consciousness revolution is coming. It’s not a thought of the future, it is happening right now.

Speak to Me / Breathe

Let’s not get too worked up, kids. There are too many benefits that can come from this for us to be foolish and self-sabotage. If we get overly excited and frame the rise of psychedelics in ways that get misconstrued, we will ruin it for everyone. Besides, all medicines are not created equally, and these have their inherent risks (as well as limitations).

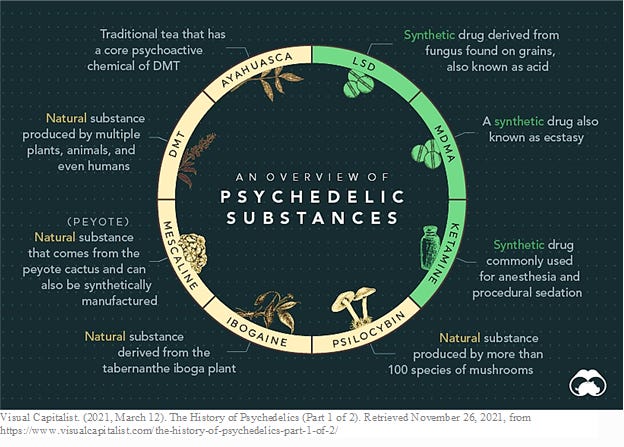

Let’s quickly run through the basics: what are psychedelics?

In simple terms, psychedelics are plant, plant-derived, and chemical psychoactive substances that produce profound cognitive and mood-altering experiences. Scientific literature evaluating the mechanisms of action of psychedelics in the brains of humans and rodents note that activation of the 5-HT2A receptor (a subtype of the serotonin receptor family) is responsible for some of the intense alterations in perception, including hallucinations, experienced upon consumption.

However, research continues to develop on how classic psychedelics and novel derivatives impact additional receptors, including 5-HT1A (serotonin), DA (dopamine), and glutamatergic (NMDA) pathways. Evidence of increased neural connections amongst a host of different areas of the brain as well as signs of neuroplasticity (neuronal growth) are also surfacing. These findings can be especially game changing for conditions like brain injury and dementia, where cell death is a major issue.

For some quick and dirty learning, check out these 2-min neuroscience videos that astutely explain the ins and outs of the human brain (including how some psychedelics, like psilocybin, work).

Given that research has just started to ramp up again, more will need to be uncovered around what exactly causes the therapeutic effects of entheogens (we’re not there just yet). There will be many opinions on this topic, including personal and environmental recommendations that influence therapeutic quality (e.g., non-drug elements, set/setting, integration methods).

What we do know is that the existing body of evidence is remarkably promising and may offer solutions to brain health in ways that we have never seen before. This provides hope to many individuals, a fresh landscape for scientific research and innovation, as well as the momentum to capitalize on investment opportunities.

On the Run

While chatting with the CEO of a psychedelics drug dev company, he playfully used the name of a famous Harvard professor as a verb, remarking that we needed to be careful in our approaches to advancing the field as to not get “Timothy Learyed.”

I appreciated that. It was clever and impactful without needing to explain much more. Nobody wants to be blacklisted, escaping from prison, or getting their operations shut down by the feds (again). Bam, 50 more years of unnecessary darkness.

But that was long ago in the 60s and 70s… we’re past that, aren’t we?

Well, in Oct 2009, Professor David Nutt, Britain’s Chief Drug Adviser and Chair of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, was fired after reporting that alcohol and tobacco were more harmful than certain other illegal substances such as ecstasy and cannabis.

Not so long ago.

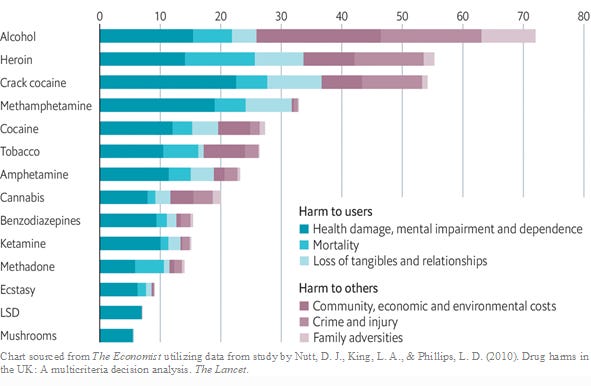

This chart highlighting views from the UK’s Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs (spearheaded by Nutt) represents data published in The Lancet shortly after his redundancy. Note that these findings continue to be substantially similar in recent research.

When looking at this, one must wonder why it has taken so long to reignite exploring things like LSD and mushrooms as potential medicines.

One glaring benefit psychedelic medicines show is low toxicity, dependence, and public harm profiles, especially relative to other common drugs and psychiatric medications. They also have side effects that tend to be manageable through proper clinical support and integration.

But that’s not the only insight here - let’s stop to consider why alcohol and tobacco are used and advertised openly without legal or social ramifications? It’s remarkable when you consider the true extent of harm - ranging from organ failure to lung cancer - caused by continued overuse of those substances.

Where’s the balance in allowing consenting adults their social freedoms while creating limitations that benefit public health? I’m not sure I have the answer.

In terms of the legal and research limitations put on psychedelics, it seems that the same stigma haunting society from speaking about their mental health has also been thrust upon a class of compounds that could have been helping millions of people. Politics and misinformed conservatism chose to protect a “war on drugs” and unnecessarily shut away important medicines that may drastically improve the wellness of humanity.

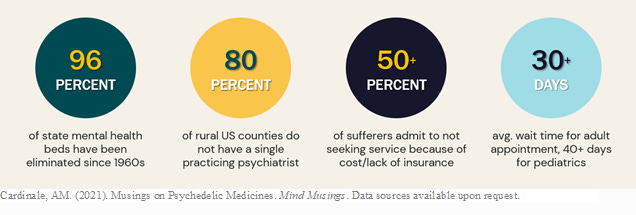

Amplify that with serious treatment limitations. Globally this is a massive issue and in the US alone:

Let’s be clear, this is not about blaming one party. This is a complex issue that requires support from many areas, including tackling our own biases. Even on the heels of a global pandemic that has created a surge in demand, a recent poll of 2,000 Americans found that 50% still view seeking therapy as a sign of weakness.

The fact is, we can all do better.

Time

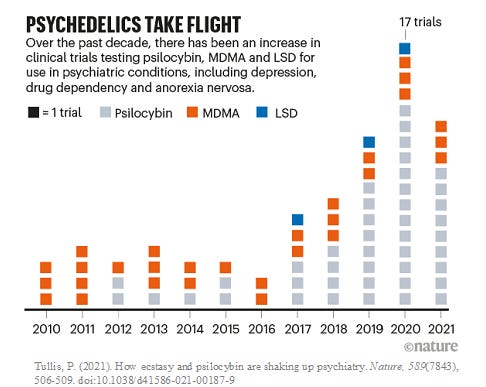

After a 60+ year hiatus, research, investment, regulation, and public discourse on psychedelics has made noteworthy breakthroughs. Although there was scarce research being conducted in the late-90s (e.g., psilocybin at Johns Hopkins and the Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich), the tide didn’t truly turn until 2011 when the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) Phase I RCT results on MDMA for PTSD were published.

This continued work led to a 2017 Breakthrough Therapy designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for MDMA therapy and approval of Phase III clinical trials that gathered widespread attention. Shortly thereafter, the FDA granted two similar designations for psilocybin - one for treatment-resistant depression (2018) and a second for major depressive disorder (2019).

Today we are seeing a multitude of patent filings, the opening of visionary research institutes, and decriminalization and legalization becoming a reality in places like Oregon and Lisbon. For more details on the journey of where we have been to where we are today, this timeline is filled with information that can really take you down the rabbit hole.

You may be wondering – what has prompted this sudden (and incredible) shift in a taboo, and somewhat feared, field?

Could it be the strong literature demonstrating benefits for those with depression, trauma, and mood disorders? Are we now getting desperate for solutions since inaccessibility and unaffordability of mental health services has erupted into a massive crisis? What about longevity, aging with independence, and the potential for psychedelics to promote neuroplasticity?

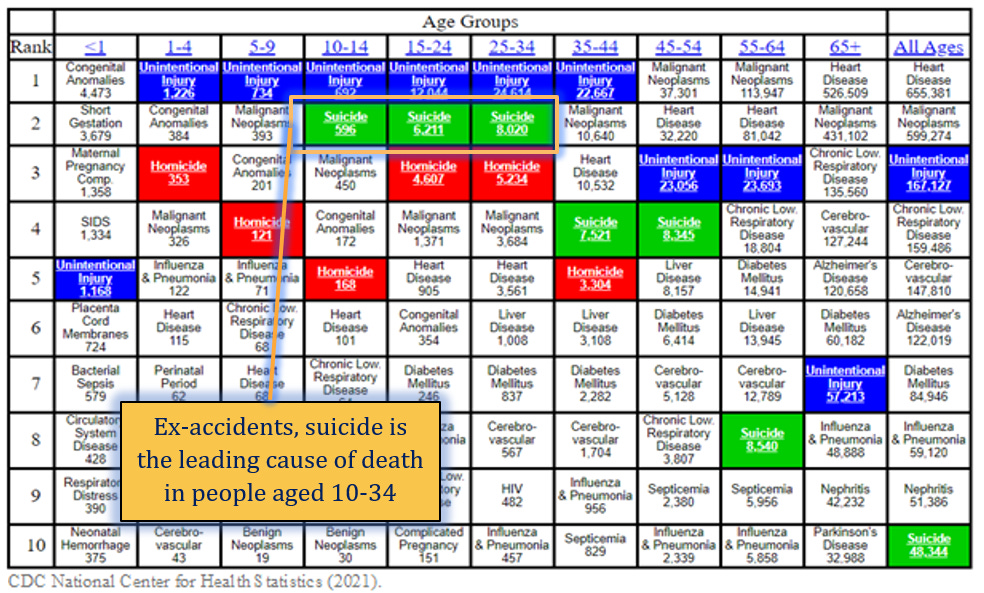

Maybe it’s the data. Mental health issues have increased dramatically since the turn of the century and 75% of countries are considered underserved in terms of mental healthcare. Depression is the #1 cause of disability globally, accounting for $1 trillion in lost productivity annually. The US has 2.5x more suicide deaths than all homicides (48k vs. 20k) and adolescent/young adult suicide rates have risen by more than 50% in the past decade.

Outside of the personal hardship experienced, this causes a propagation of socioeconomic issues for employers (missed days of work, longer use of disability benefits), health systems (more ER visits, increased hospital stays), and families (financial issues, suicidality). These ripple effects, including the overcrowding of prisons with individuals who should be receiving health care instead of incarceration, tends to get attention after a while.

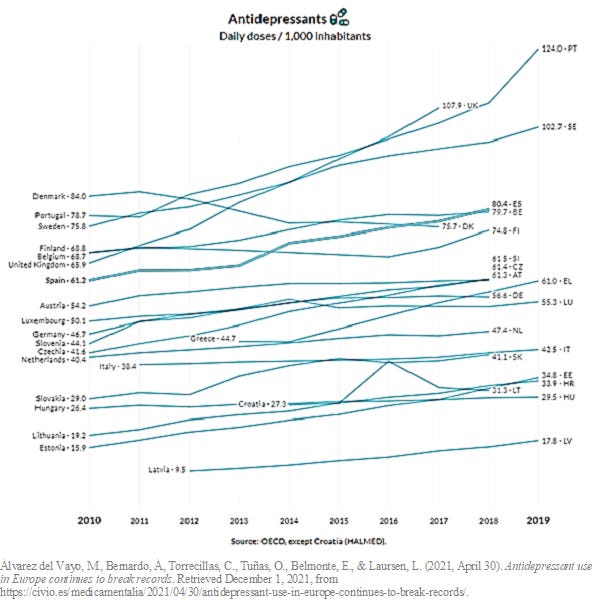

Now is the time to expand our treatment protocols to encompass more than commonly used antidepressants, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines that have remained unchanged for 3 decades and are increasingly prescribed without a proper diagnosis.

Please don’t get me wrong - existing mental health medications definitely have their benefits. There’s a lot of writing out there advocating for psychedelics while bashing current psychotropic treatment options. It’s not that SSRIs and benzos don’t work… there’s plenty of evidence to show that they can be helpful for certain populations.

Some of the main issues are that they don’t have rapid onset, usually require ongoing dose and type tweaks for each individual, as well as come with a laundry list of side and withdrawal effects. Shorter term (<12 mos) medication use generally helps control symptoms, however longitudinal research on the efficacy of antidepressants is a widely debated topic in psychology circles. There is mounting evidence that long-term use may produce poor outcomes and certain researchers believe that loss of clinical effect is neurobiological and not solely a factor of depression severity and relapse.

However, we shouldn’t forget that people must take their medication properly (up to 50% don’t) and should be given talk therapies in conjunction with medications. Unfortunately, ~5-10% of Europeans, Britons, and Americans are prescribed meds but only 1-3% of them receive talk therapies (and the vast majority are not given guidance on how to get it).

For some, choosing that little pill is a “lesser of the evils” strategy… short term pain to get out of a bad time and then hopefully moving on. For others, it’s a lifetime of medication switching, feeling numb, risking addiction, and potentially never getting to the root of the issue.

The Great Gig in the Sky

So, what exactly happens when sacred tradition, amateur experimentation, and concrete science come together?

Cosmic love.

Research is accelerating at a rapid pace and government bodies are opening to discussions on how to support studies evaluating medicinal use cases of psychedelic compounds. For example, the NIH just gave $3.9mm to Johns Hopkins to study psilocybin therapy for tobacco addiction. It’s said that this is the federal agency’s first grant to research a classic psychedelic in over 50 years, however, earlier this year there was also a $190k career development grant given to a Yale researcher to study psilocybin as a potential treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder.

Below are selected research papers on the usefulness and impact of psychedelics that have occurred since the turn of the century. This does not represent an all-inclusive list, rather is meant to highlight a variety of medicines and certain noteworthy milestones.

2000: Dr. Marcus E. Raichle, neuroscientist and professor at Washington University School of Medicine, describes a default mode of brain function after performing PET to measure blood oxygen levels in resting vs. goal-oriented action states. This becomes the basis for further research into the Default Mode Network (DMN) that is known to be downregulated with the use of psychedelics and believed to be tied to introspective thought, ego, and social cognitive processes.

2006: Dr. Roland Griffith of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine leads the publication of a double-blind RCT (n=30) evaluating the psychological effects of a high dose of psilocybin (30mg) vs. placebo immediately after and 60 days following a course of 2-3 sessions delivered ~2 months apart. Perceptual and quickly oscillating emotional changes were found (including an increase in anxiety), however substantial personal and mystical/spiritual significance was the largest outcome experienced by the participants. In follow-up reporting, sustained positive changes in attitudes and behavior were disclosed in questionnaires and findings were consistent with ratings by community observers who acted as third-parties evaluating changes in participants' attitudes and behaviors.

2011: MAPS Phase I RCT (n=20) on MDMA-assisted therapy for treatment resistant PTSD shows clinically significant improvement in intervention group CAPS scores (a widely used clinically-administered PTSD assessment) and stress severity. The rate of clinical response was 10/12 (83%) in the active treatment group versus 2/8 (25%) in the placebo group. There were no drug-related serious adverse events, however, in the week following sessions, some of the most common side effects - fatigue, anxiety, low mood, headache and nausea - were reported at similar incidence in both groups. Anxiety was found to be slightly more frequent in the MDMA group and low mood slightly more frequent in the placebo group. Although the MDMA is integral to this treatment process, it’s important to note that most of the therapy provided did not involve MDMA. Rather, 2 sessions covering 5-6 hours of treatment used the drug and 11-14 non-drug sessions + 180 min of preparation were administered.

2014: In a double-blind RCT (n=12), a team of European and American researchers evaluated LSD for anxiety associated with life-threatening illness. Participants were asked to lie on a mattress or sit in a chair for two 8-hour sessions and were either given 200μg or 20μg (active placebo) of LSD. The experimental dose was a moderate amount expected to produce the full spectrum of a typical LSD experience without completely dissolving ego structures while the 20μg dose was an active placebo expected to produce short-lived and mild LSD effects that would not substantially create therapeutic impact. After each active session, 3 drug-free psychotherapy sessions occurred, and the participants’ experiences were reviewed for integration (processing and deepening the therapeutic process). Two months after the second treatment, state (event-driven) and trait (personality-related) anxiety scores were significantly lower in the LSD vs. the placebo group and remained stable at 12-month follow-up.

2016: Shortly after conducting a small study on the antidepressant qualities of ayahuasca, researchers from the University of Sao Paulo report findings from administering a single dose of ayahuasca to 17 psychiatric inpatients with recurring depression. No psychotherapy was given following the session and patients were discharged 24 hours later. Significant decreases in multiple depression-related scales were found and average HAM-D scores dropped by nearly 12 points from moderate to mild depression levels in follow-up measures conducted 21 days later. Because the results were not randomized, placebo-controlled, or double-blinded, the researchers encourage others to replicate their work in this fashion and to consider if adding ceremonial rituals could improve therapeutic outcomes.

2021: Compass Pathways completed the largest RCT to-date studying psilocybin for a mental health condition. The double-blind placebo-controlled study (n=233) evaluated a single dose of their derivative compound, COMP360, across 25mg and 10mg interventions vs. 1mg controls for treatment-resistant depression (TRD). The 25mg dose relative to controls showed that 30% of participants had a significant reduction in the MADRS depression scale with most sustaining this until week 12. However, the 10mg dose failed to show any significant difference from 1mg. These are positive top-line results but some issues with safety data signal the need for more research to be completed. Across the intervention groups, ~14% of patients experienced side effects like suicidal behavior and intentional self-injury, albeit this is a common risk with a difficult population that is typically resistant to treatment. Note that earlier in the year, a Phase II RCT (n=59) comparing psilocybin with the common SSRI escitalopram did not find a significant difference in antidepressant effects between the treatment groups, but the study does highlight it as an effective alternative to the drug.

For more information on compounds and evidence-based literature, Psychedelic Science Review is an excellent resource to follow as work in the field develops. You can also find drug development companies’ clinical trial progress via this tracker from Psilocybin alpha.

Current findings are incredibly promising and have the potential to greatly change psychiatry, mental health care, and treatment of neurological conditions. With all of this said, more research is still needed into long-term outcomes, optimal care models, novel compound safety, and the broader public health impact of psychedelics. By supporting research, we can deepen our understanding of therapeutic use cases, provide data to inform regulatory decision making, and help determine the safest and most effective ways to apply the benefits of psychedelics to the wellness of broader society.

Stay tuned for Part II where we will cover investment and innovation in the field.

Salute,